Parodied and appropriated arguably more than any other movie image, Boris Karloff’s lumbering neck-bolted monster exists in our pop culture memories in a manner approaching religious iconography. No one needs to have seen Frankenstein to recognize the image of the film’s monster, and while we’re aware the creature’s name isn’t really Frankenstein, most of us are still okay with calling him that anyway. (In the film, Henry Frankenstein even calls him “Frankenstein” once as a kind of paternal desperation.) With the world of Wikipedia, there is also a general awareness that this visually iconic film has almost nothing in common with the Mary Shelley text upon which it’s based; another schism we tolerate in favor of convenience and tradition.

So, then what is the famous film Frankenstein other than a pop collection of contradictions? Is it, like its monster, simply a patchwork of dead parts of culture, constantly reanimated by our incorrect assumptions and hell-bent on punishing for our willful ignorance and revisionism?

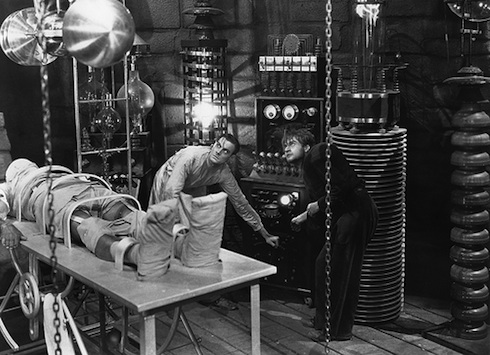

If a film like King Kong is a theatrical, meta-fictional, and somewhat realistic fantasy, then Frankenstein is straight-up surreal and romantic melodrama intended to make you uncomfortable. And while the notions of a ranting mad scientist, a creepy hunchback assistant, and lumbering killer (sporting big shoes, a bad haircut and serious forehead) are all singed into our brains, it’s a little surprising to discover almost none of these images have much of an explanation. The motivations of characters aren’t even remotely clear. Why is Henry Frankenstein so determined to create a patchwork person and reanimate such a creature with lightning? We’re never told. How did he come to employ Fritz, the initially loyal, and then later reckless and cruel hunchback? It’s not explained, nor does it make any sense whatsoever. Fritz is there for two plot reasons: to steal the wrong brain (a criminal brain instead of, say, the brain of a poet laureate) and then later, to torment the Monster with fire and a whip until the Monster murders him. In this way, Fritz has as much function as any of the other characters, they all either cause something to happen because the story just goes that way, or they’re put into peril because we need some other people for the Monster to fuck with. Luckily, Mary Shelley’s novel didn’t have characters this thin or it would have never been adapted into this iconic movie with really thin characters who lack any real motivation or reliability!

Wait. Is this movie terrible? No! Because the movie Frankenstein is the perfect reflection of the image you have in mind of Frankenstein. Frankenstein isn’t a movie; it’s more of a mood. And that mood isn’t just created by imagery, but maybe even more so, by sound. If our contemporary critics bemoan the overuse of computer-generated effects in the spectacles of today, I can totally hear a critic of 1931 bitching about the wall of sound Frankenstein shoves onto its audience. There’s a reason why Mel Brooks constantly had the sounds of thunder interrupting the dialogue of characters in Young Frankenstein. In Frankenstein, the sound of thunder practically forces the characters into certain actions.

Of course, there is a plot reason for this: the lightning bolts are the stuff that breathes life into the monster, though we never actually see the lighting strike the corpse, we hear it instead. Over and over again. This works because, the thunder is ominous, and it and other sound effects are as important as the film’s characters. In a film that is essentially a romantic horror, designed to make you feel like you’re watching something macabre and perverse, these sound effects in concert with the jerky black and white camera work succeed at unnerving anybody who is watching the movie out of the corner of their eye. I’d assert if you wanted to make everyone at a party very, very uncomfortable, the audio from Frankenstein would suffice.

But then there’s Karloff himself. The soundless close-ups director James Whale employs when the monster is first revealed to us are a perfect combination of an actor’s performance and great filmmaking. Could Karloff have pulled this off without the bolts in his neck and the rest of the iconic get-up? You bet.

Considering that he has no lines, Frankenstein’s monster is easily the most interesting character in the film. Here, a little bit of justice is done to the novel because from just one glance we immediately understand the anger and complex emotion raging beneath the surface of the monster. Despite assumptions to the contrary, Karloff doesn’t play this as one-note as you might think. As silly as it sounds, I can’t overstate the subtlety of his performance enough. At 70 minutes, Frankenstein is a mercifully short film and every second given to Karloff is exactly the right amount and he does wonders with what was, I imagine, a fairly vague script.

Surprisingly, the Monster doesn’t kill that many people. In fact, his body count is exactly three, and only one of those murders was premeditated. You could argue he kills Fritz in a kind of self defense because even the characters seem eager to convince each other that Fritz had it coming. When the Monster kills Dr. Waldman, any normal audience member is practically rooting for him, because if he never gets out of that place, then this ominous and spooky movie will end up having a happy ending! In another turn that is reminiscent of the novel, the Monster makes an attempt on the life of Frankenstein’s fiancé, though he for whatever reason leaves her alive. (I would argue the filmmakers should have had the monster kill her too, as it would have made Frankenstein’s motivations to go help the mob kill the Monster a little stronger.) But Elizabeth and Henry will survive the rest of the film, and the last victim the Monster claims is that of a little girl; Maria.

Putting aside how it is essentially the exact opposite of what happens in the book, this scene might be the best one in the movie. While the Monster is wandering through the “countryside” (Don’t even try to think where this takes place in the real world. Is it Germany? I mean, everybody is called either “Herr” or “Fraulein,” but often it’s with a Brooklyn accent!) he happens upon a little girl and her kitten. They’re picking flowers, and the little girl, eager to make friends, shows the Monster that the flowers float on top of the water when thrown. In a brilliant moment of tenderness, the Monster throws a few flowers onto the water and exhibits genuine joy. Then, in a move straight from Steinbeck, he picks up Maria and throws her into the water. This is the Monster’s final “murder,” and it’s an accident caused by a misunderstanding. Now the movie has shifted from romantic horror and melodrama to traditional tragedy. Like so many other monster narratives, someone else is to blame here, and it’s certainly not the Monster. He was just trying to have a good time.

This scene is shot wonderfully too, and the fact that it takes place in broad daylight is way more frightening than any of the scenes of the Monster lumbering in the dark. The iconic final scenes on the windmill are wonderfully dark, and the brief face-off between Frankenstein and his creation send literal chills up my spine as I write these words. When the two glimpse each other through the machinery that causes the windmill to rotate and you briefly associate this kind of mechanism with all the pulleys and levers in Frankenstein’s lab, it becomes pretty clear these filmmakers knew exactly what they were doing.

Tragically, the film ends on a faux-happy note, with Frankenstein’s father, Baron Frankenstein, drinking some wine with his house servants while his son and fiancé recover. While the attempt at levity here is preposterous, the fact that we don’t actually see Frankenstein’s face nor Elizabeth’s, is actually fairly genius. The audience is left to believe that the only person living in the delusion that everything will be okay now that the Monster is dead is Frankenstein’s blowhard father. If the film ended with Henry and Elizabeth getting married anyway, all the work of the movie would have truly been undone. Instead, everything ends on a light touch, a contrast to the artistic camerawork and innovative sound effects that pervade the rest of the film.

It’s not a perfect film, but watching it today, even with the monstrous shadow of its reputation, I get the sense that this movie and the images it spawned are victims of their own success. This movie created more than one monster, and maybe that’s a good thing.

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com.

It might be petty to mention this, but those things in the monster’s neck are not bolts – they’re electrodes.

@1 So noted!

As I understand it, the happy ending was tacked on at the last minute. The movie originally ended with Henry dying.